Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

A dissertation that explores the early attachment and maternal voice preference in one- and three-day-old infants. The research focuses on the newborn's ability to discriminate and prefer their mother's voice, using studies and experiments to support the findings. The document also discusses the potential impact of these preferences on infant-mother bonding.

Typology: Lecture notes

1 / 53

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction.

300 N. ZEEB ROAD, ANN ARBOR, Ml 4810618 BEDFORD ROW, LONDON WC1R 4EJ, ENGLAND

8118773

FIFER, WILLIAM PAUL

The University of North Carolina at Greensboro PH.D. 1981

University Microfilms International 300 N. Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48106

This dissertation has been approved by the following committee of the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

Dissertation Adviser

Committee Members

April 24, 1981 Date of Acceptance by Committee November 13, 1980 Date of Final Oral Examination

n

FIFER, WILLIAM P. Early Attachment: Maternal Voice Preference in One- and Three-Day-Old Infants. (1981) Directed by: Dr. Anthony J. DeCasper. Pp. 45 Human newborns between thirty-four and ninety-six hours old were tested in a discrimination procedure designed to measure prefer ence for the maternal voice. Sucking bursts initiated during one auditory stimulus resulted in presentation of a recording of the mother's voice, while sucking during another signal was followed with the voice of the previous subject's mother. Once a voice was produced it remained on for the duration of a burst. Newborns kept their mother's voice on longer than the other female's voice. In addition, the probability of responding was greatest during the signal associated with the maternal voice. Current theories of attachment do not predict this phenomenon.

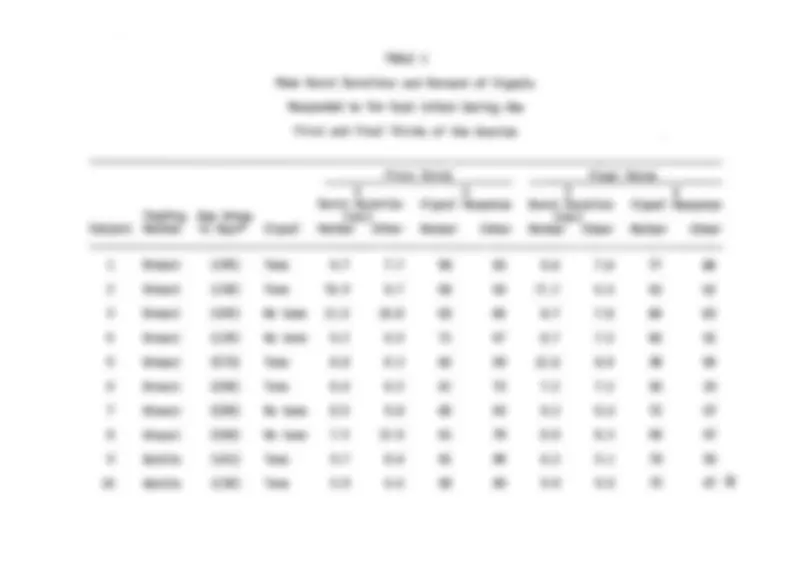

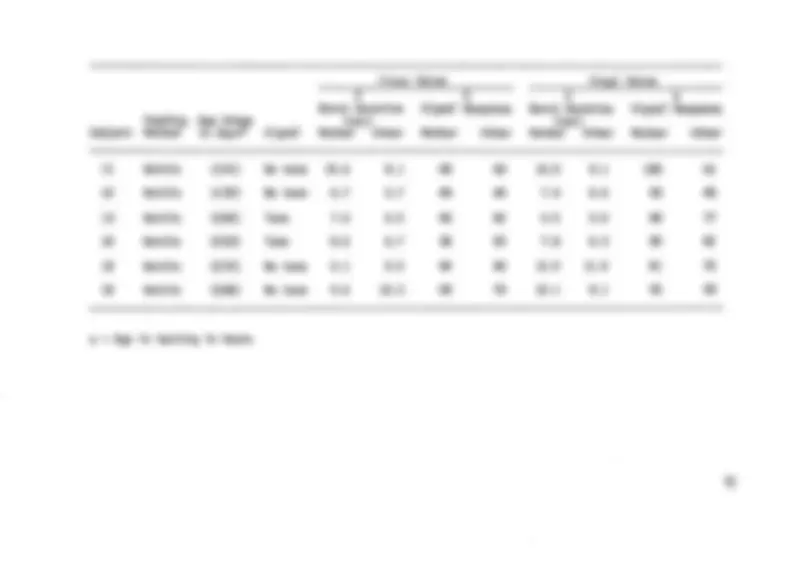

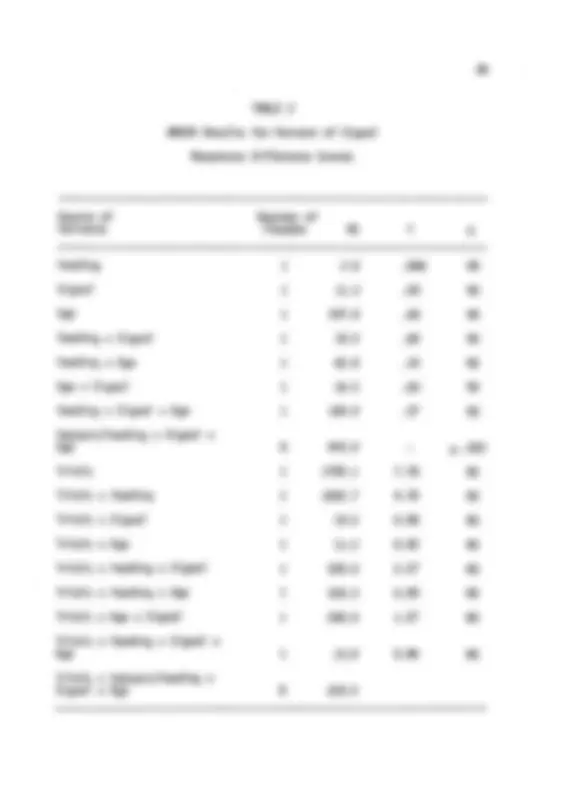

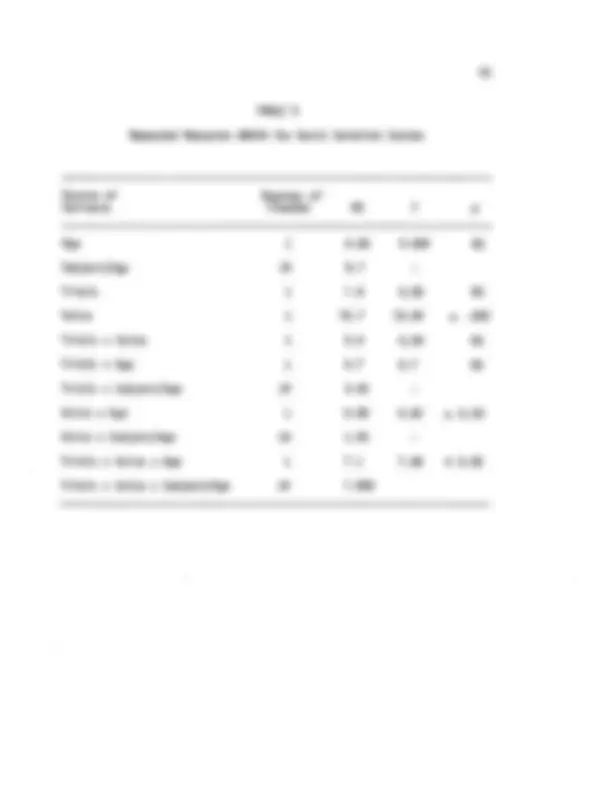

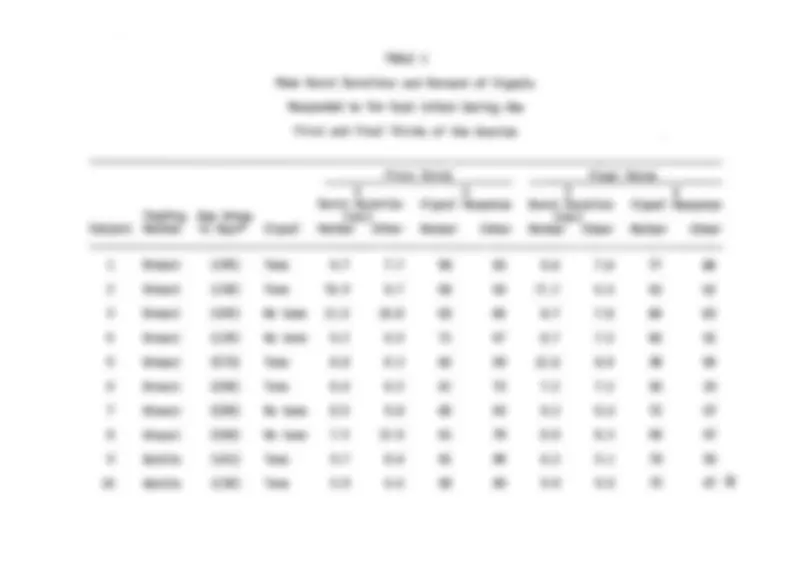

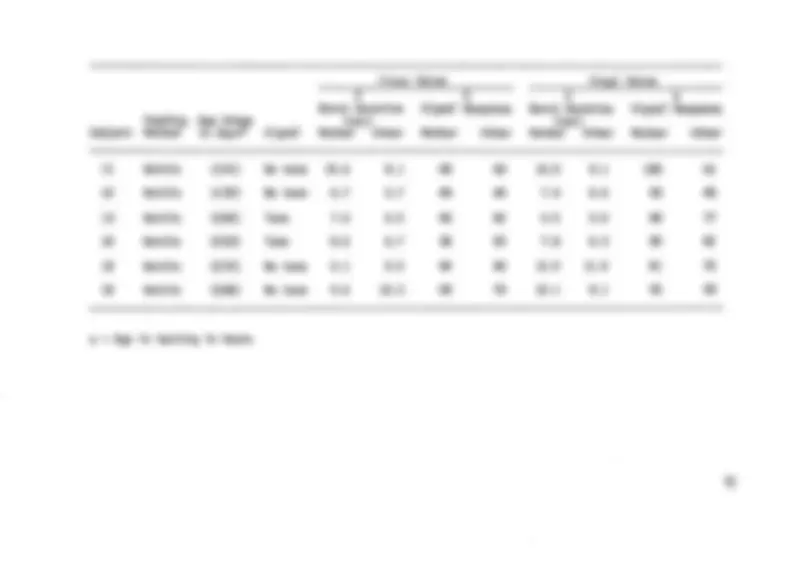

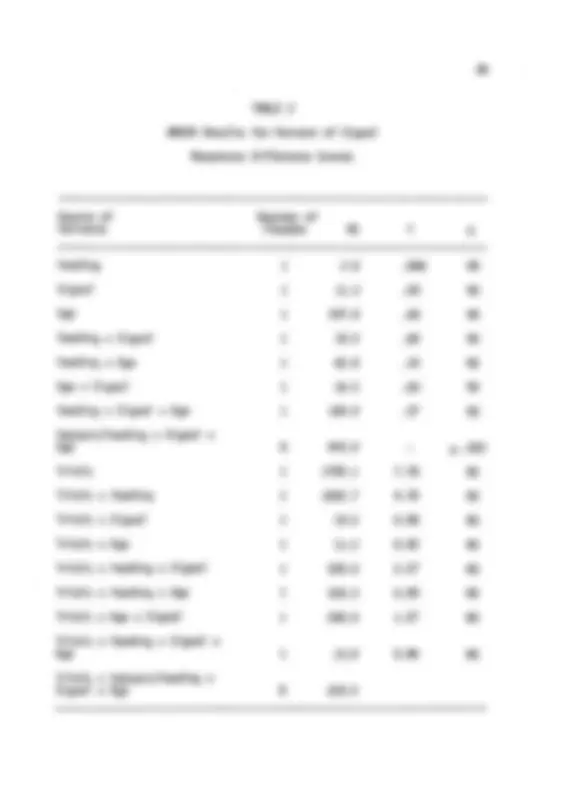

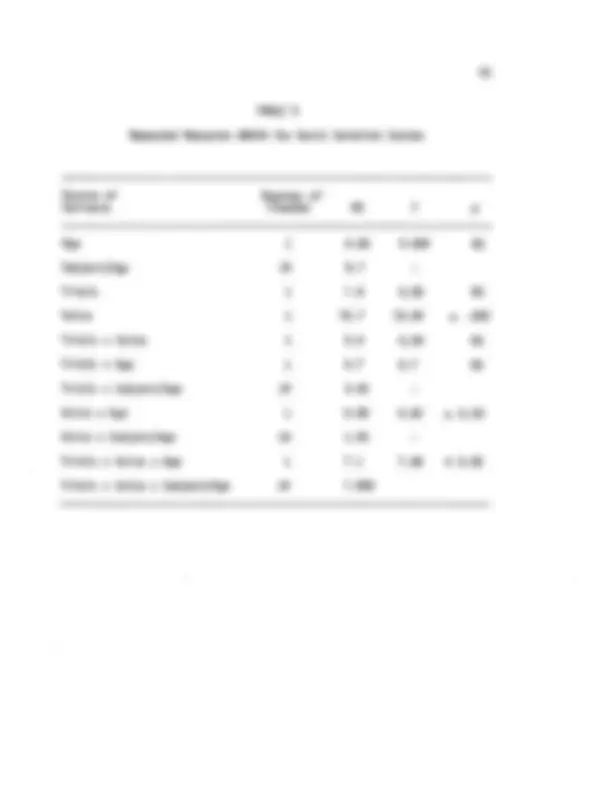

Page TABLE 1 Mean Burst Durations and Percent of Signals Responded to for Each Infant During the First and Final Thirds of the Session 36 2 ANOVA Results for Percent of Signal Responses Difference Scores 38 3 Repeated Measures ANOVA for Percent of Signal Responses 39 4 ANOVA Results for Burst Durations Difference Scores 40 5 Repeated Measures ANOVA for Burst Druation Scores 41

iv

Page FIGURE 1 The Mean Percent of Signals Associated With the Maternal Voice and the Other Voice That Were Responded to During the First and Final Third of the Session 43 2 The Average Difference Scores in Seconds of Burst Durations Associated With Mother's Voice Minus Durations With the Other Voice for the FirstAnd Final Thirds of the Session 44 3 The Average Burst Durations in Seconds Associated With the Maternal and the Other Voice for One-Day- Old and Three-Day-Old Infants During the First and Final Third of the Session 45

v

2 Bowlby (1969) described the attachment process as the sine qua non for infant survival. The infant's highly adaptive proximity-seeking behaviors serve not only to establish proximal interactions, e.g., the clasp reflex of rhesus monkeys or the rooting reflex of humans, but also more distal ones, e.g., eye contact, smiling or following behav iors. According to Bowlby, proximity-promoting behaviors function in three ways: (1) as orientation behaviors (rooting, visual following) to direct the infant's attention to and allow tracking of those stimuli which are most likely to emanate from humans; (2) as signaling behav iors (crying, smiling, babbling) to attract the adult into proximity with the infant; and (3) as approach behaviors (crawling, clinging, searching) to allow the child to follow and approach the mother. Child-mother attachment is described by Bowlby and Ainsworth as developing in four phases (Bowlby, 1969; Ainsworth, 1972, 1979). The first stage is labeled the "initial preattachment phase." During this stage infants show no evidence of discriminating one person from another. Rather, the infant's repertoire of orienting and signal behaviors has been characterized as "largely reflexive" (Bowlby, 1969), "protosocial" (Newson, 1977), and reflecting mainly "thermal, reflexive, nutritive, and hormonal processes" (Cairns, 1972, p. 57). The first phase begins at birth and continues until the infant shows the ability to discriminate among individuals. The second phase, called "attachment in the making," does not begin until the infant reaches eight to twelve weeks of age (Ainsworth, 1979; Bowlby, 1969; Eisenberg, 1979). During this phase signaling and orienting, along with proximity seeking behaviors such as visually

3 coordinated reaching, become focused on one or a few individuals, typically the mother. Phase two is thought to last until the child is six or seven months old. Phase three is characterized by unmistakable attachment to the primary caretaker. That is, the infant incorporates various active strategies in order to seek contact and maintain proximity. For example, the mother is used as a home base from which the infant explores his/her surroundings (Rheingold & Eckerman, 1970). During these forays the infant spends much of his/her time establishing visual or auditory contact with mother. This phase lasts well into the third year, after which time the infant becomes more skilled at adjusting his behaviors to the mother, becomes sensitive to the mother's goals and needs, and enters into what Bowlby labels the final attachment state, a partnership. Most research on attachment has centered on the final two phases of attachment and on determining criteria for measuring the infant's attachment, e.g., latency in establishing contact, average distances from caretaker, and responses to strangers, novel environments and separation (Ainsworth & Wittig, 1969); Ainsworth, 1972; Bell, 1968; Cairns, 1977; Corter, 1977; Rheingold & Eckerman, 1970; Shaffer & Emerson, 1964). However, most research on the early stages of attach ment has focused on maternal behavior. Thus, there is a gap in our understanding of the sequence of the attachment process from the infant's perspective. The need to examine the infant's early role in the attachment process has been frequently cited (Bower, 1974; Brazleton, 1978; Gerwitz, 1972; Klaus & Kennell, 1976). Ainsworth

5

discriminate and show a preference for an odor associated with mother. Newborns will turn their head significantly more often and for longer periods of time toward a breast pad soaked with their own mother's milk rather than toward a simultaneously presented pad soaked with another woman's milk (McFarlane, 1975). The newborn's ability to respond to vestibular and proprio ceptive stimulation may also facilitate sensitivity to cues associated with mother. Neonates are most visually alert and most easily soothed in an upright position while being rocked (Korner & Grobstein, 1966; Korner & Thoman, 1970). More recent evidence points to the actual movement cues, the change to the upright position, as the critical variable in enhancing visual attentiveness (Gregg, Haffner, & Korner, 1976). In this same study infants who were sucking on a pacifier were more visually alert than those without pacifiers. In addition, infants ten days of age appear capable of using proprioceptive, in combination with other, cues for discriminating the handling and feeding style of the primary caretaker, i.e., infants showed marked distress and disrup tion of normal feeding patterns when multiple caretakers were substi tuted for the primary caretaker (Birns, Sander, Stechler, & Julia, 1972). Several researchers have recently suggested that these sensory competencies and stimulus preferences subserve a number of develop mental processes, particularly infant-mother bonding (Brazleton, 1978; DeCasper & Fifer, 1980; Eisenberg, 1976; Klaus & Kennell, 1976 ; Korner& Thoman, 1970). Early discrimination of and attachment to significant others could be served if the infant was maximally and differentially

6

sensitive to different types of maternal stimulation. The previous discussion suggests newborns are indeed sensitive to proximal cues- odor, touch, nearby visual stimulation. However, since indices of attachment primarily consist of the infant's responses to maternal presence or absence in the auditory or visual field, a differential sensitivity in the newborn to more distal cues may more directly subserve the attachment process. Specifically, early discrimination and preference for mother's voice might serve to facilitate the development of the reciprocal interactions essential in the mother- infant bonding process. The human newborn's auditory system appears especially useful for detecting cues potentially associated with mother. Indeed, even the fetus is capable of responding to auditory events by the final trimester of gestation and has shown gross body movement and electro- encephalographic and heart rate changes to extrauterine noises (Eisenberg, 1976). Other evidence for precocious auditory competency is observed in studies showing both behavioral and electrophysiological responding to sound in preterm infants (Eisenberg, 1976; Gregg, Haffner, & Korner, 1976). Newborn infants will orient toward a sound source (Wertheimer, 1961) and, as Leventhal and Lipsitt (1964) have shown, are sensitive to the direction of the sound source. Body move ment and change in respiration habituated to a tone presented from one direction and recovered when the direction of the sound source was changed. Newborns' auditory capabilities also include a sensitivity to frequency and band width components of human speech. For example,

8

1976). For example, cues associated with intonation and rise-and-fall time of a tone are discriminated by young infants (Morse, 1972). Condon and Sander (1974) demonstrated that newborns move in synchrony to human speech. This entrainment apparently involves a sensitivity to the prosadic features of speech, e.g., intonation, inflection, temporal patterning, in that synchrony was not demonstrated with clicks or disconnected vowel sounds. The capacity to discriminate the phonetic components of speech, which has been demonstrated in young infants (Eimas, 1975), also appears to lie within the newborn's range of capa bilities (DeCasper, Butterfield, & Cairns, 1976). These perceptual sensitivities undoubtedly subserve a number of auditory preferences displayed by newborns. For example, instrumental music can be distinguished from a wideband noise and the infant will actually work, i.e., alter his rate of sucking when such a change pro duces the music (Butterfield & Siperstein, 1972). Similar techniques show newborn preferences for vocal over instrumental music and speech over other nonspeech sounds (Eisenberg, 1976; Siperstein & Butterfield, 1973). Ashmead and Lipsitt (in preparation) demonstrated the newborn's heart rate decelerates to female voices but not to male voices. Con sistent with this finding is the observation that older infants show a preference for the female over the male voice (Brazleton, 1978). Miles and Meluish (1974) showed that the maternal voice may be an important stimulus for older infants; they demonstrated a differen tial sensitivity to the maternal voice in infants 20 to 30 days old. In their procedure^ six-minute contingency training period in which sucking resulted in presentation of a variety of unfamiliar voices

9 preceded two three-minute testing periods. For a third of the infants, sucking during the first testing period produced the mother's voice. Sucking during the next period was followed by presentation of the stranger's voice. A second group experience a reverse order of test ing and a third group received noncontingent voices. Amount of time spent sucking and number of sucks per minute were greater when a brief presentation of mother's voice followed initiations of sucking bursts. In a study using one-month-old infants (Mehler, Bertoncini, Bauriere, & Jassik-Gershenfeld, 1978), sucks were reinforced with either mother's or a stranger's intonated voice or either voice presented in monotone. A significant increase in sucking was only observed when mother's voice was properly intonated. Though these procedures clearly demonstrate that infants respond differentially to their mother's normal voice, the differences in responding do not necessarily indicate a preference for her voice, i.e., a differential sensitivity to a stimulus need not indicate a preference for that stimulus. Clinical observations, e.g., Andre'-Thomas (1966) and Hammond (1970), have suggested that newborn infants will preferentially orient to mother's voice. However, not until a recent study by DeCasper and Fifer (1980) was there any direct experimental evidence that neonates prefer their mother's voices. In their procedure,48- to 72-hour-old infants were observed for five-minute baseline periods in which sucks on a nonnutritive nipple were recorded and the median time between sucking bursts was determined. A burst was defined by a series of sucks separated by less than two seconds. For one-half of the infants, interburst intervals (IBI) less than the baseline median were followed

11 have been revealed by longer sucking bursts with the maternal voice. However, during baseline and reinforced sucking, there was a weak positive linear correlation between interburst intervals and succeeding burst durations (see also DeCasper & Hill, inpreparation). Although the correlation was weak, independence of interburst interval and burst duration was uncertain. The correlation may have obscured effects of the burst length presentation time relationship and/or interfered with learning the contingency, especially with younger infants. Pilot studies using the IBI contingency indicated that the one- and two-day- old infants were less likely to sustain a full 20-minute session. Further study suggested that changing from the IBI contingency might increase the time that younger infants could be tested and also facilitate acquisition of the burst during contingency. An auditory discrimination procedure was developed in which the presence or absence of a tone signaled the availability of the different voices, but voices still remained on for the duration of a sucking burst. Because interburst intervals are nondifferentially reinforced, the duration of each burst (the amount of time each voice is maintained) may serve as an additional independent measure of preference. Thus, the likelihood of responding in the presence of each signal serves as one measure of preference and the duration of sucking bursts in the presence of each voice serves as another. The second purpose of this study was to investigate the role of newborn experience on the attachment process; specifically, the possible effects that feeding practices may have on maternal voice preference. Benefits to health and nutrition are known to result

12 from successful breast-feeding. Methods of feeding may also affect the early bonding process. For example, breast-feeding, as opposed to bottle-feeding, results in longer duration of feeding (Bernal & Richards, 1970), more fluid consumption (Klaus & Kennel!, 1976), more crying prior to feeding (Bernal & Richards, 1970), more eye contact during feeding (Abercrombie, 1971), and more rapid development of regular feeding cycles (Lozoff, Brittenham, Trause, Kennel!, & Klaus, 1977). These factors could affect both the amount and quality of vocal inter actions between mother and infant and perhaps subsequent bonding. Third, the newborn's neuronal and physiological systems rapidly adjust to requirements of the extrauterine environment (Smith & Bierman, 1973). Such changes over the first postnatal days of life have been observed to affect the newborn's patterns of sucking and sleeping and the frequency of crying and feeding (Lozoff et al., 1977; Roberts, 1977). Thus, the amount and quality of maternal contact during the early postnatal days may also be affected by changes in the infant's state and response patterns (Klaus & Kennel!, 1976). The third pur pose of this study then is to consider the ontogeny of preference for mother's voice by examining age differences during the first four days of life. The potential effects of age and feeding method are, of course, confounded with other variables, particularly the amount of time spent with mother. However, with a demonstrated effect or lack of effect of these variables on voice preference and a consideration of their under lying factors would offer important information for understanding the development of attachment to the maternal voice and infant-mother