Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

A research paper by Jonathan B. Pritchett and Herman Freudenberger from Tulane University, exploring the relationship between transport costs and relative prices of slaves in the New Orleans market. The authors discuss the impact of transport costs on the selection of slaves for shipment and the resulting price differences in different markets.

Typology: Study notes

1 / 29

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

Appendix to A Peculiar Sample: The Selection of Slaves for the New Orleans Market

by Jonathan B. Pritchett and Herman Freudenberger

Department of Economics Tulane University New Orleans, LA 70118

Preliminary version

Alchian and Allen's theory is based on fixed transport costs lowering the relative price of higher quality goods at distant markets. While we have shown in previous research that traders incurred considerable costs in transporting slaves, we have not shown what impact these costs had on the relative prices of slaves in New Orleans. 1 In this following section, we show that the slave trader's "markup" is a decreasing percentage of the purchase price of the slave, which is consistent with a fixed component of transport cost. Furthermore, the percentage markup is higher on children than on prime-aged adults, lowering the relative price of these latter slaves at the point of destination. The lower relati v e price for prime-aged slaves provides the motivation for the slav e trader's shipment of higher qualit y s l aves to New Orleans.

Matched Sales Records In the long run under competition, the difference between the price of a slave in the ex porting state and his price in New Orleans should equal the cost of transportation plus the slave trader's normal profit. However, the prices of slaves sold in New Orleans reflects not only transport cost but also the trader's selection of higher quality slaves for shipment to that distant market. A simple comparison of slave prices in different markets would therefore over-state the percentage markup since the slaves shipped to New Orleans were, on average, of higher quality than the slaves sold in the local markets of the ex porting states. Furthermore, we argue in the text that the effects of selection varies systematically with age, in that traders chose only the tallest children for shipment whereas traders chose to ship both tall

records span the 1840's and 1850's. While the accounts of these traders include more transactions over a longer time period than our matched Maryland sales records, they typicall y provide us with less information about the slaves who were sold. For ex ample, the trading accounts of Tyre Glen often omit the age of the slave who was sold. This is particularly true of the children. The youngest slave for which we have information on purchase price,

resale price and age is nine years old. Thus our results for the impact of transport costs on relative prices may not be applicable for the youngest children who were sold by slave traders. Did slave traders charged a constant percentage markup on the slaves that they purchased and subsequently resold? We can answer this question by regressing the purchase price in the ex porting state on the resale price at the point of destination. If transport costs increase in proportion to the purchase price of the slave, then a one percent increase in the purchase price of the slave should increase the resale price by one percent. If, however, transport costs did not increase in proportion to the slave's value, then the elasticity of the resale price with respect to the purchase price should be less than one. Regression results for the matched Maryland sales records and the Tyre Glen trading records are presented in Table A-1. For both sources of data and for all trading seasons, the coefficient on the natural log of the purchase price is less than one, varying from 0. 69 for the 1830/1831 trading season to 0.89 for the 1831/1832 trading season. In addition, the estimated elasticities are significantly less than one for five of the seven trading seasons listed in Table A-1. These findings imply that a one percent increase in the purchase price of the slave increased the resale price by less than one percent. Or, by implication, the relative price of the higher valued slaves was less at the point of resale than at the point of purchase. We have yet to establish, however, that the percentage markup on prime- aged slaves was less than the percentage markup on younger slaves. Unfortunately, the accounts of Tyre Glen list the ages for only 65 of the 193 slaves for which there is information on both purchase and resale price. In

from the certificates of good character but also the heights listed on coastwise manifests in that the slaves listed on both documents were presumably measured three different times, by different officials and at different places.

Truncation a nd Systematic Mismea sur e ment The Louisiana legislature only required the certification of imported slaves aged 12 years or more. Given that potential buyers did not know the ex act age of a child offered for sale, the y ma y have been forced to infer the slave's age by his or her respective height. 6 The certification of slaves was costly. 7 Traders may have attempted to avoid this cost by only providing certificates of good character for children who are obviously aged twelve years or more. Given that height and apparent maturity are positively correlated, selective certification would result in an upward bias in the estimated heights of the sample of certified slaves. In other words, since small children would not be certified, the children who were certified would tend to be taller on average than children from the general population. In addition, the ex tent of this bias would be less for older slaves, since relatively few slaves aged 15 years could be represented by traders as onl y 11 y e a rs old. Thus the apparent differences in th e mean heights of adolescent slaves found in Tables 1 and 2 may have been due to the selective certification of taller slaves rather than the selective purchases by slave traders. The partial truncation of a distribution of heights is a common problem in the use of records from organizations with minimum height requirements. Various techniques have been developed to correct for such deficient data, the

most common of which is to inspect for a shortfall in the lower tail of the age-specific height distribution. 8 While we find no evidence of such a lower-tail shortfall, this need not imply there was no upward bias in the measured heights of certified slaves. There was no minimum height requirement for certification. Instead , buyers presumably inferred age through the o bservable characteristics of the slave, only one of which was height. Without such a height standard, the extent of the upward bias in the measured heights of certified slaves can only be estimated through a comparison of h e ights drawn from another sample of slaves. Age-specific mismeasurement of heights may also explain the observed difference between the two samples. The slaves listed on the certificates of g ood character were measured in different counties across the South whereas presumably the heights of slaves transported coastwise were calculated and recorded in the ports of departure. Different measurement procedures could have resulted in systematic differences in the measured heights of slaves. If , for example, slaves were measured with their shoes on then the average h e ight of slaves would be overestimated by this amount. In addition, the me asurement bias may vary with the height, and hence the age, of the slave. While we know relatively little of the procedures followed in the measurement of slaves, it has been suggested that slaves may have stood in front of a measuring stick attached to a wall. Such a procedure may have resulted in parallax problems in making the measurements. Since the extent of this bias depends on the height of the observer relative to the slave, the heights of short slaves may have been systematically underestimated while the heights of tall slaves may have been systematically overestimated. 9 While we cannot rule out the possibility of such systematic biases in

is not a perfect subset of the sample of slaves recorded from the certificates of good character since some of these slaves were re-exported to other markets whereas other slaves were sold on later dates. 10 As may be seen in Tables A- 3 and A-4, the heights of slaves recorded in the certificates of good character were quite similar to those recorded on the traders' manifests. The results from the Smirnov test statistic indicate that the samples are significantly different for only 3 of the 28 age/sex categories listed in the Tables A-3 and A-4. The slaves listed on the certificates of good character were taller for two of these categories whereas the slaves listed on the coastwise manifests were taller in one of the categories. While there are some differences, the heights of slaves in these two samples appear to be remarkably similar. An implication of the above comparison is that slaves carried by coastwise traders were of similar stature to the imported slaves sold in the New Orleans market. This is an important result given that traders sometimes transported slaves for a fee to New Orleans, even though their owners did not intend to sell them at their final destination. The equal stature of the slaves in these two samples would seem to indicate that most slaves transported by traders were intended for sale. The close similarity in heights between the certified slaves and the slaves listed on the traders' manifests also allows us to rule out partial truncation as a possible source of bias. There was no selective measurement of slaves listed on the manifests given that federal law required the measurement of slaves of all ages who were transported coastwise. In addition, shippers had no incentive to either misrepresent the heights or ages of the slaves on the manifests. 11 The absence of truncation bias in this

sample, along with its close similarity to the sample of certified slaves, implies that the adolescent slaves shipped by slave traders were indeed taller than those found on other coastwise manifests.

PLANTATION SIZE AND THE HEIGHTS OF SLAVES Plantation size provides an alternative explanation for the greater observed height of the slaves listed on the certificates of good character. Richard Steckel finds health conditions deteriorated with plantation size which, he argues, would have reduced the attained height of slaves from larger holdings. Based on data drawn from Civil War muster rolls, Margo and Steckel find that black recruits originating from counties with larger slave holdings tended to be shorter on average than black recruits from other counties. Furthermore, Steckel argues that slaves flowed from smaller to larger farms, given the increased concentration of slave holdings over time. Since the slaves from small farms were more likely to be traded than the slaves from large farms, one would expect the heights of slaves shipped by traders to be greater than those of the general slave population. 12 The question of plantation size may be addressed through a subset of our sample of certified slaves. As mentioned previously, each certificate of good character lists the name of the previous owner of the slave in addition to providing the place of certification. Slaves who were sold in New Orleans in 1830 were linked to the 1830 manuscript census using published indexes on the basis of the first and last names of the previous owner and the county of certification. Duplicate names within a county and owners residing in counties other than the one of certification were eliminated. By linking the slave sold in New Orleans to her household in the exporting state, we are able

owner's holdings are included in the subsample. The regression equations are specified to include two dummy variables for plantation size. Medium size holdings are classified as holdings with 10 to 49 slaves whereas large size holdings are defined as holding with 50 slaves or more. The results from Table A-7 indicate that holding size had little or no effect on the heights of adolescent slaves sold in New Orleans. Male slaves from medium sized holding were slightly shorter than slaves from small holdings whereas male slaves from large holdings were. 5 inches taller. However, neither of these coefficients are statistically different from zero. The lack of a relationship between heights and holding size seems to also apply for the regression for female adolescents. The signs on the coefficients were the exact opposite to those in the previous regression and both were statistically insignificant. While this may indeed imply no relationship between the heights of slaves and plantation size, it may also be the case that slaves sold by owners were not representative of the general slave population. If so, it is not surprising that we find no relationship between holding size and the heights of slaves.

THE HEIGHTS OF NON-TRADED SIAVES Michael Tadman has recently argued that the slaves who were not identified as shipped by traders, whom we classify as "non-traded" slaves, were themselves a select group, and therefore not representative of the general slave population. In particular, planter migrations, which would have brought a "true-cross section of Upper-South slaves," account for relatively few of the non-traded slaves shipped to New Orleans. Rather, the great bulk of the non-traded slaves were private purchases by planters or their agents, the crews of ships, hired hands and work gangs and the servants who

accompanied travellers. These slaves would have contributed to "the upward bias in the minority of New Orleans shipments which are not attributed to identifiable traders." Tadman goes on to argue that the manifests of non- traders do not under-represent the stature of infants and young children but rather that the source of upward bias lies with adults listed on these manifests. In particular, the male slaves selected by both traders and other shippers were of greater stature, from which he concludes that "the real average height of adult males was significantly" less than 5 feet, 7 inches. 13 As stated in the text, we know relatively little about the slaves who were shipped by others than identified traders. The extent of the bias created by treating all non-traded slaves the same can be estimated by comparing the slaves transported by migrating planters with the slaves shipped by other non-traders. In an effort to identify the manifests of migrating planters, we adopt a procedure originally outlined by Tadman in his dissertation. 14 First, we exclude all slaves transported coastwise by identifiable traders. Second, in order to exclude the crews of ships, servants who accompanied travellers, and "small-scale purchases by unidentified traders and by private individuals," we exclude all manifests which list less than 10 slaves. Finally, in an effort to exclude hired slaves, we exclude all manifests where males constitute 70 per cent or more of the slaves aged 20 to 29 years. The average height of the remaining slaves are then compared with the slaves from the excluded categories in the following table. Note that slaves are classified by both sex and age group in order to allow for variation in trader competition across different classes of slaves.

Maryland Slaves

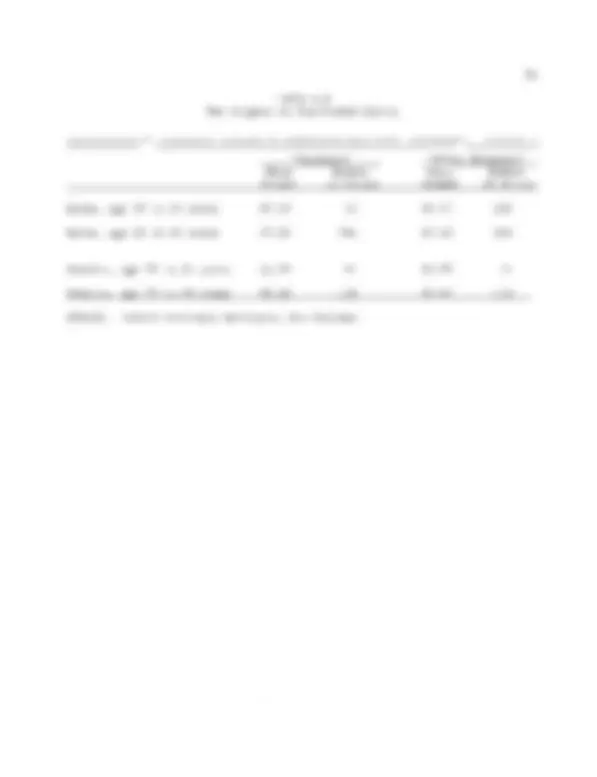

Table A- Percentage Markup on Interstate Slave Sales Regression Analysis

18 29-1830: log (sale price) 2.035 + 0.725 log (purchase price)a (0. 439) (0.076) n= 34, R^2 =0.747, mean sale price=$519, mean purchase price=$ Tyre Glen trading r ecords 1830-1831: log (sale price) 2.009 + 0.686 log (purchase price) (0.878) (0.157) n=25, R^2 =0.453, mean sale price=$360, mean purchase price=$ 1831-1832: log (sale price) = 0.928 + 0. 892 log (purchase price) a (0.225) (0.039) n= 34, R^2 =0. 942, mean sale price=$448 , mean purchase price=$ 1832-1833: log (sale price) = 1.761 + 0.759 log (purchase price)a (0.354) (0.060) n=42, R^2 = 0.798, mean sale price=$500, mean purchase price=$ 1833-1834: log (sale price) = 1.323 + 0.849 log (purchase price) (0.957) (0.160) n= l2, R^2 =0.738, mean sale price=$606, mean purchase price=$

1834-1835: log (sale price) = 1.320 + 0.834 log (purchase price)b (0.357) (0.058) n=l8, R^2 =0.927, mean sale price=$620, mean purchase price=$

1837-1838: log (sale price) = 1.368 + 0.857 log (purchase price)b (0.365) (0.056) n=62, R^2 = 0.747, mean sale price=$1134, mean purchase price=$

SOURCE: Maryland Slaves, Certificates of good character & Maryland State Archives; Ty re Glen Pa pers, Duke University, Durham, NC. NOTE: a, b The regression coefficient is significantly different from 1 at the 1% and 5% levels respectively. Standard errors in parenthesis.

Maryland Slaves Percent Markup= 1.

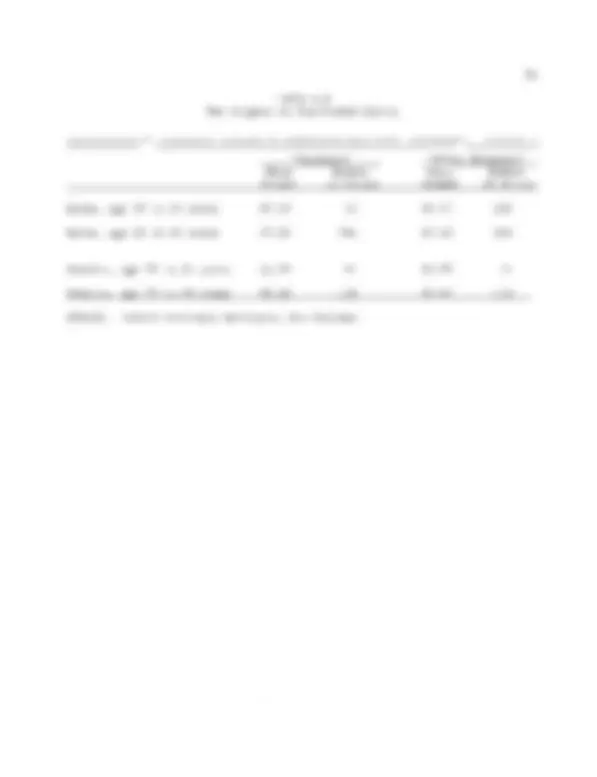

Table A- Percentage Markup by Age Regression Analysis

Archives; Tyre Glen Papers, Duke University, Durham, NC. NOTE: a, b The regression coefficient is significantly different from 0 at the 5% and 10% levels respectively. t-statistics in parenthesis. The dependent variable is defined as follows: Percent Markup = (resale price - purchase price) / purchase price

Table A- Height by Age for Female Slaves

Certificates of Good Character Traders' Manifests Age Mean Std. Dev. Obs. Mean Std. Dev. Obs. Difference in Means 12b 57 .07 2.79 14 53.59 1. 95 19 13 56. 88 3. 44 28 57.18 2.93 20 -0. 14 60.06 2.78 57 59.16 2.59 25 0. 15 61. 62 2. 38 71 60.98 2.13 41 0. 16 61. 93 2.40 102 61. 36 2.25 88 0. 17 62.23 2. 87 77 62.68 2. 22 68 -0. 18 62.76 2.79 93 62.62 2.56 61 0. 19 63.18 2.50 48 63.04 2.43 42 0. 20b 62. (^78) 2.90 54 63.45 2.15 33 -0. 67 21 62.56 1. 98 12 63.33 1.10 12 -0. 77 22 62.50 3.15 22 63.47 2.13 19 -0. 23 62.07 2.59 15 62.61 3.07 7 -0. 24 63.09 3.50 20 63. 96 2.54 (^7) -0. ages 25-49 63.03 2.59 87 63.07 2.34 58 -0. SOURCE: Certificates of good character (cols. 2-4) and Inward Coastwise Manifests for identified New Orleans traders, 1829-1830 (cols. 5-7). NOTE: a The mean height of the sample of certificated slaves is significantly greater than mean height of slaves sampled from the coastwise manifests at the 5% level. b The Smirnov two-sided test statistic indicates that the samples of slaves for this age are significantly different at the 5% level.

Table A- Classification of Slaveholders by Size of Holdings

1 to 9 slaves 10 to 49 slaves SO slaves and Over Entire South, 73. 5% 24.3% 2. 3% 1850 Sellers of 42.6% 49.8% 7.6% Slaves, 1830 SOURCE: calculated from U.S. Bureau of the Census, Seventh Census of the United State, 1850 Compendium (Washington, 1854), p. 95; Certificates of ~ood Character and manuscript census records, 1830.

Entire South, 1850

Slaves Sold, 1830

Table A- Distribution of Slaves and Slaves Sold by Size of Holdings

to 9 slaves 10 to 49 slaves 26 .6 % 51. 8%

SOURCE: L. C. Gray, History of Agriculture in the Southern United States to 1860, 1 (Washington, 1933), p. 530; Certificates of Good Character and manuscript census records, 1830.