Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

The relationship between sport-confidence trait, competitive orientation, and sport-confidence state using data from the Sport Confidence Inventory (TSCI) and the Competitive Orientation Inventory (COI). The study found that sport-confidence trait was a significant predictor of sport-confidence state, as well as a negative relationship with external locus of control, competitive A-trait, cognitive competitive A-state, and somatic competitive A-state. The document also discusses the construct validity of the TSCI and COI, and the results of Pearson correlational analyses and Student-Newman-Keuls post hoc analyses.

Typology: Exercises

1 / 26

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

JOURNAL

OF SPORT PSYCHOLOGY,

1986,

8,^ 221-

An interactional, sport-specific model of self-confidence was developed inwhich sport-confidence

was

conceptualized

into trait (SC-trait)

and state (SC-

state) components. A competitive orientation

construct was also included in

the model to account for individual differences in defining success in sport.In order to test the relationship represented in the conceptual model, an in-strument to measure SC-trait (Trait Sport-Confidence Inventory or TSCI), an^ instrument

to measure SC-state (State

Sport-ConfidenceInventory or SSCI),

and

an^

instrument to measure competitive

orientation (Competitive

Orienta-

tion Inventory or COI) were developed and validated. Validation proceduresincluded five phases of data collection involving

high school, college,

and adult athletes.

three

instruments demonstrated adequate item discrimi-

nation, internal consistency, test-retest reliability, content validity, and con-current validity.

In^ the construct validation phase, the results supported several

predictions based on the conceptual model.Sport psychologists have traditionally adopted three approaches

in studying

self-confidence in sport. Bandura's (1977) self-efficacy theory has been used topredict behavior by measuring individuals' efficacy expectations (Feltz, 1982;Feltz, Landers,

Raeder, 1979; McAuley

Gill, 1983; Weinberg, Gould,

Jackson, 1979; Weinberg, Gould, Yukelson,

Jackson, 1981; Weinberg, Yu-

kelson,

Jackson, 1980). Conceptual models of perceived competence

(Harter,

1978; Nicholls, 1980) have also been adapted to sport in an attempt to predictachievement behavior in that context (Feltz

Brown, 1984; Roberts, Kleiber,

Duda, 1981; Spink

Roberts, 1980). Other researchers have used perfor-

mance expectancies to operationalize

self-confidence and attempt to predict be-

havior in sport (Corbin, 1981; Corbin, Landers, Feltz,

Senior, 1983; Corbin

Nix, 1979; Nelson

Furst, 1972; Scanlan

Passer, 1979, 1981).

Research based on these theories has contributed a great deal to the sport psychology literature. However, significant advances in the

of self-confidence

Requests for reprints should

be^

sent to Robin S. Vealey, Dept. of HPR, Phillips

Hall, Miami University, Oxford, OH

^1 Vealey await sport-specific conceptualization and measurement instrumentation. Self-efficacy has been operationalized in countless ways for every situation that hasbeen studied. An earlier attempt to parsimoniously operationalize self-efficacyin sport situations proved low in predictive validity (McAuley

Gill, 1983) for

the most part because the constructs

represented physical self-concept as opposed

to self-confidence in sport ability. Harter's operationalization of perceived com-petence is based on a developmental approach and her instrumentation is validonly for children. Nicholls' distinction between ego-involved and task-involvedperceived ability has yet to be operationalized. Research on expectancy, like self-efficacy, has developed countless

scales for the myriad of situations

in which ex-

pectancy is of interest. Based upon this past research, it seems that a valid, par-simonious operationalization of self-confidence would allow more consistentprediction of behaviors across different sport situations. Thus, it is the purposeof this study to provide a theoretical

model in which self-confidence may be con-

ceptualized based on the unique context of sport and develop valid instrumenta-tion to measure the constructs conceptualized in the model.

nificant developments in personality research. It seemed appropriate to concep-tualize a model of self-confidence based on the interactional paradigm, sport-specificity,

the distinction between personality traits and states, and the reciprocity

of individual differences and behavior. Because the construct being conceptual-ized is not general self-confidence but sport-specific self-confidence, the term"sport-confidence"

was adopted.

To aid in the conceptualization of sport-confidence, the literature on self- efficacy,

perceived competence, and perfo&mce expectancy

were perused. Build-

ing from these constructs, sport-confidence was defined as

the belief or degree

of certainty individuals

possess about their ability to be successful in sport.

But

as Maehr and Nicholls (1980) have stressed, success means different things todifferent people. Thus, attempting to predict behavior by measuring sport-contidence

also requires measuring the goal upon which sport-confidenceis based.

It seemed important, therefore, to include in the model a construct based uponthe goals that individuals strive for when they compete. The term "competitiveorientation" was established to indicate

a tendency for individuals to strive

toward

achieving a certain type of goal in sport. Evidence supports the existence of goalorientations in sport (Ewing, 1981;

Kidd &Woodman, 1969; Mahoney

Petrie,

1972; Snyder

Spreitzer, 1979; Webb, 1969) and nonsport (Nicholls, 1980)

Obviously, any number of goals could be operating for different

individuals

when competing in sport. However, sport-confidence is grounded in perceptionsof ability, thus the competitive orientations

should reflect an athlete's belief that

attainment of a certain

type of goal demonstrates competence and success. For

this reason, performing well and winning were selected as the goals upon whichcompetitive orientations

are based. Athletes, of course, may pursue both of these

goals simultaneously; they usually strive to play well and win at the same time.However, one goal may be more important to an athlete

the other. Achiev-

1 3 ~ s

(^) 1 3 s ~

(^) may

(^) ' 1 3 ~ s

(^01)

(^) y l y ~ hy-

(^) SB

(^) r (^) l (^) )

(^01)

(^) 1 3 s

(^) 1 3 s ~

(^) PUV

S l f m U U n (^) ptl (^) SlSaJ

P (^) V

l0S

-ws

(^) (3)

' 0 3 ~ s

(^) ' ( I ~ s J ,

(^) JO

3uaumrlsuI L.mu!uqaq

(^) IOU (^) d

(^03)

(^) d

MOI

(^01)

(^) y l y ~

(^01)

(^) d

(^) 0%

(^) ayl

(^) m

(^01)

(^) ig

(^) a n p a a d

IOU

(^01)

(^) U I

y l y ~

(^03)

(^) ayl

(^) se

(^01)

(^) y l y ~

Sport-Confidence and Competitive

Orientation

coz

A major consideration

in developing a format for the COI was the extreme

reactivity of the performance-outcome distinction. It seemed that most athleteswould say they would rather perform well

than

win. However, the orientation

they publicly endorse and the goal they strive

for in the heat of competition may

be completely different. Therefore, a measurement format was needed in whichathletes

would not have to directly choose one orientation over another. It seemed appropriate to develop a type of format that would force athletes to weigh thevalue of both goals simultaneously.

Based on these considerations, a matrix format was adopted for the COI (see Appendix A). The matrix contains 16

cells that represent different situations

in sport. One dimension of the matrix (rows) establishes different levels of per-formance (very good, above average, below average, very poor), and the otherdimension (columns) establishes different outcomes (easy win, close win, closeloss, big loss). Thus, each cell represents a situation that combines a certain out-come with a certain level of performance. Athletes were directed to completethe matrix by assigning a number from

unsatisfying situation" and 10 represents a "very satisfying situation."

The scoring

procedure devised for the COI is a variance analysis approach

based on the columns-by-rows design of the matrix (see Appendix A). The out-come orientation score (COI-outcome) is computed by dividing the

sum

of squares by the total sum of squares. This score represents the proportion oftotal variance occurring

across different outcomes. That is, COI-outcome reflects

how much athletes' feelings of satisfaction vary based on whether they win orlose. The range of COI-outcome is

(low) to

(high). High COI-outcome

represents a high outcome orientation.

The performance orientation score (COI-performance) is computed by dividing

the

row

sum of squares by the total sum of squares. This score represents

the proportion of total variance based on differences

in performance. Specifical-

ly, COI-performance represents how much athletes' feelings of satisfaction varybased on whether they perform well or poorly. The range of COI-performanceis .00 (low) to 1.

(high).

High COI-performance

represents a high performance

orientation.

The purpose of Phase 1 of the study was to assess (a) the internal structure of the inventories,

(b)

individual item characteristics,

and (c) the degree to which

Two hundred subjects participated in Phase

sample consisted of

subjects, of which

were female and

were male.

All high school subjects were members of scholastic basketball teams and themean age of the sample was 16.6 years. The college/adult sample consisted of46 males and

females. Of the

subjects,

were college basketball play-

ers, 30 were college swimmers, and

were road racers. The mean age of this

sample was 20.2 years.

(^) 1 3 s ~

l ~ q

(^) u~oy

(^01)

(^) s!

(^) 13s.~

I@

(^) npns (^) '

(^39)

(^01)

(^) SEM

(^) '13~s

(^) 1 3 s ~

(^) J U ~ ~ I J J ~ O ~

(^) '0s'

(^) 13~s

(^) 1 3 s ~

(^) JOJ

SBM

(^) op

(^) ~13~s

(^) =

(^) =

(^) =

(^) '(1s (^) =

(^) =

(^) =

(^10) (^) '(6s (^) =

(^) = u)

(^) SEM

(^) 0s

(^) pan lo nu.^

leu

MOI

(^) M

(^01)

(^) 1 3 s ~

(^) JOJ

(^) 13~s

(^) 13s~

^1 Vealey

The participants in Phase 3 were 219 subjects, consisting

of 109

high

school

athletes of which 88 were female and 21 were male. The college sample consist-ed of 110 athletes of which 32 were female and 78 were male. Subjects in bothsamples were members of physical education

classes and had participated in some

form of competitive sport. The mean ages for subjects were 17.1 years for thehigh school sample and 20.4 years for the college sample.

The high school and college samples were divided into three groups. Group 1 in each sample was administered the TSCI and COI and then readministeredthe same inventories 1 day later. Group

TSCI and COI and then readministered the same inventories 1

week later. Group

3 in each sample was administered the TSCI and COI and then readministeredthe same inventories 1 month later. Three investigators carried out the testing,but all retests were administered by the investigator who made the initial

contact.

All investigators

read the same set of instructions each time the inventories were

For the TSCI, the following reliability coefficients were obtained: 1 day (r^ =

.86), 1 week (r

= .89), and 1 month (r

= .83). The results indicated that

test-retest reliability (r

= .86 across time and samples) for the TSCI was well

above the accepted .60 criterion (Nunnally

following reliability coefficients were obtained: 1 day (r

= .69), 1 week (r

=

.69), and 1 month (r

= .69). For COI-outcome, the following reliability coeffi-

cients were obtained: 1 day

(r^

=^ .69), 1 week (r

=^

.69), and 1 month (r

=^

Across times and samples, both COI-performance (r

=

.69) and COI-outcome

(r^ =

.67) met the accepted criterion. These analyses

indicated

that sport-confidence

and competitive orientation, as operationalized by the TSCI and COI, are fairlystable dispositions that may be measured across time.

Concurrent validity determines the effectiveness of a test in predicting

Subjects used in this phase were those who participated in Phase

study (n

=

199). Group A consisted of 59 high school athletes and

college

athletes

=^

103). Group

high school athletes and 52 college

athletes (n

=

In a noncompetitive situation, subjects in Group A were administered the

230

^1 Vealey

Table

2

Pearson Correlation Coefficients for the SSCI

Construct

N^

r

Competitive A-traitPerceived physical abilityPhysical self-presentation confidenceExternal locus of controlCognitive competitive A-stateSomatic competitive A-stateSC-state (CSAI-2)SC-trait^ " ' p

.001;

_ * p_*

.

The correlations between the SSCI and other constructs are listed

in Table

Several of the correlations were significant in the predicted direction.

SC-state was positively related to SC-trait, SC-state measured by the CSAI-2,and physical self-presentation confidence. SC-state

was negatively related to com-

petitive A-trait and both cognitive and somatic competitive

A-state. Again, sport-

confidence was more strongly related to cognitive anxiety than somatic anxiety.SC-state

and external

locus of control were not correlated significantly,

nor were

SC-state and perceived physical ability.

COI-performance

was significantly

related in a positive direction to

SC-state as operationalized by the SSCI, r

= +^ .29;

p^ <

COI-outcome was

significantly related in a negative direction to SC-state as operationalized by theSSCI, r

=

This evidence suggests that the goals athletes focus

on when competing (competitive orientation)

are related to precompetitive sport-

confidence. Specifically, focusing on performing well is related to higher levelsof SC-state, and focusing on winning and losing is related to lower levels ofSC-state.

A low but significant positive relationship emerged between COI-perfor- mance and physical self-presentation confidence, r

= +^

p^ <

This result

suggests

that performance orientation

is related to confidence in displaying phys-

ical ability and having that ability evaluated by others. Clearly, defining compe-tence and success by performance is related to approaching the highly evaluativeenvironment of sport with confidence.

Finally, COI-performance was significantly correlated in a negative direc- tion with external locus of control, r

=

and COI-outcome was

significantly correlated in a positive direction with external locus of control, r^ =^

A positive characteristic of performance orientation is the con-

trol over competence and success that it creates. Outcome orientations are notconducive to perceptions of control over success because winning and losing insport are highly unstable and uncontrollable outcomes. Thus, it is logical thatperformance orientation is negatively related and outcome orientation positivelyrelated to external locus of control.

Sport-Confidence and Competitive Orientation

COI-performance and COI-outcome were not significantly related to SC- trait, competitive A-trait, cognitive and somatic A-state, SC-state measured bythe CSAI-2, and perceived physical ability. It is difficult to explain why com-petitive orientation was significantly related to SC-state measured by the SSCIand not related to SC-state measured by the CSAI-2. It may

be based on the differ-

ent operationalizationof self-confidence

in the SSCI as compared to the CSAI-2.

The SSCI seems to tap individuals' cognitive appraisals about how their abilitywill compare to the demands of a specific situation. The CSAI-2, on the otherhand, seems to tap somatic and cognitive reactions to the cognitive appraisalprocess. This is evident in such CSAI-2 items as

feel at ease," "I feel com-

fortable,"

and "I

feel secure."

This conceptual difference between sport-

confidence

as measured by the SSCI versus the CSAI-2 may have accounted for

the different relationships

between competitive

orientation and SC-state as mea-

sured by the two inventories.

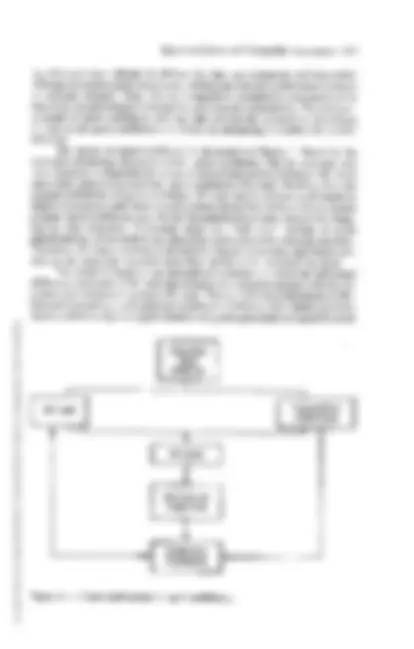

The task in construct validation is to provide evidence that an instrument operationally defines

the construct it was designed to measure. This involves testing

the adequacy of hypothesized relationships

between the construct being validat-

ed and other constructs in the theoretical model.

construct validation model

was developed to illustrate the theoretical

relationships

to^ be

examined (see Figure

2). The theoretical

constructs

and their relationships

are shown above the broken

line, and the relevant operational definitions of these constructs and their rela-tionships are shown below the broken line.

any validation process it is neces-

sary to assume some links are valid while testing other links. Figure

-^ Construct validation

model.

Conceptual

SC-trail

3

Behavioralresponses

CompetitiveOrientation

4

11

-^ - -^ -^ - -^ - -^ -

,

-^

-^ --.

-^ -

-^

-^ -

TSCl

Measures

2

Behavioralmeasures

Other Individual

Situational

Other

difference factors

factors

factors

InfluencingSC-state

Influencing

lnlluencing

operationalized

SC-state

behavior

Operational

Other indlvldualdifference

factors Influencing SC-state

SiluatlonalfactorsinfluencingSC-state

Other factorsinfluencingbehavior

Sport-Confidence

and

Competitive

Orientation

H7: High SC-trait performance-oriented athletes rate their performancehigher than high SC-trait outcome-oriented, low SC-trait performanceoriented, and low SC-trait outcome-oriented athletes.H8: High SC-trait performance-oriented athletes are more satisfied withtheir performance than high SC-trait

outcome-oriented,

low SC-trait

per-

formance-oriented, and low SC-trait outcome-oriented athletes.

because the theoretical

construct (SC-state) is operationalized (SSCI) in this link.

Construct validation of the SSCI involves examining Link

tionships represented by other links in the model. Specifically, relationshipsrepresented by Links 2 and 9 were examined.

Influence of SC-Trait and Competitive Orientation on SC-State.

Link 2

was discussed earlier as the degree

to which SC-trait and competitive

orientation

predict SC-state (see Figure 2). This relationship

will

not be discussed again here,

but it is important to realize that the prediction of SC-state from SC-trait andcompetitive orientation (using their respective operationalizations) also providesconstruct validity for the SSCI.

The

Ability ofSC-State to Predict

Behavior.

The second link in the model

examined to assess the construct validity of the SSCI was Link 9 (see Figure 2).This links represents the degree to which SC-state predicts behavior. Link 9represents the predictive validity of the SSCI to predict behavioral responses-itis the operational level of Link 10. To the extent Link 9 is supported, it is possi-ble to infer construct validity, assuming Links 10 and 11 are valid and Link 12is controlled. Thus, this phase of the study examined how well the SSCI

predicts

sport

behavior. The sport

behavior measured in this study was performance. The

following hypothesis based on Link

in the model was tested:

H9: SC-state is a significant predictor of performance.

Subjects for this phase of the study were

elite gymnasts participating

in the U.S. Gymnastics Federation National Meet. Of the total, 28 subjects weremale and 20 were female. They ranged in age from 15 to 25 years; the overallmean age was 19.

years. The mean age for females was 17.7 years and the mean

age for males was 21.1 years.

Twenty-four hours prior to competition, athletes completed the TSCI and COI. Also at this time, athletes

completed a questionnaire that recorded age, com-

petitive experience, and perceptions of past success

in^ gymnastics. Approximately

hours prior to the first round of competition,

athletes completed the SSCI.

No later than 2 hours after the first round of competition, athletes were againadministered the SSCI. Also at this time, athletes rated their performance andsatisfaction with performance, and provided causal attributions for it. The per-formance scores used in the study were mean scores computed from the athletes'performances from the first round of competition. The investigator obtained ob-jective performance scores from the meet judges.

Table

Normative Data for the TSCI, COI, and SSCl

Sample

N^

M^

Median

Low

High

SD

=

p^ <

=

<^ .001, and COI-outcome and precompetitive

=

<^ .001. Significant correlations also emerged between

=

<^ .001, COI-performance

=

p^ <

r^ =

<^ .006.

236

^1 Vealey^ No interaction emerged between SC-trait and competitive orientation for postcompetitive SC-state using similar analysis of variance procedures. However,a significant main effect occurred for SC-trait, F(l, 43)

=^

p^ <

.001, with

high SC-trait athletes (M

=^

=

=^ 24) higher in postcom-

petitive SC-state than low SC-trait athletes (M

=^

=^

Also, a main effect emerged for competitive orientation, F(l, 43)

=

p

=

=

=

in^ postcompetitive

SC-state

than outcome-oriented

athletes (M

=^

=^

=^ 23). Thus, although no interaction emerged for postcompeti-

tive SC-state, the findings indicate that both SC-trait

and competitive orientation

influence this variable.

Influence o

f SC-Trait and Competitive Orientation on Outcomes.

Simple

correlations representing the relationships between SC-trait, competitive orien-tation, and subjective outcomes are shown in Table 4. These correlations pro-vide partial support for Hypotheses 3 and 4. Because the validation model predictsthat SC-trait and competitive orientation

interact

to influence subjective

outcomes,

2 (highllow TSCI)

ance were employed using the four subjective outcomes as dependent variables.As before, median splits were used to dichotomize

the TSCI and COI-performance

variables into high and low groups (see Table 3 for median splits of elite sample).

Table

4

Pearson Correlations of Subjective Outcomes

with SC-Trait, Performance Orientation, and Outcome Orientation

Performance

Outcome

SC-Trait

orientation

orientation

Internal attributions

.42***

.73*

-.69***

Performance rating

.^

.42*

-^ **.33****

Performance satisfaction

.^

**.53*****

-^ .46***

Perceived success

.55*

*^

.^ -^.

The first subjective outcome examined was causal attributions for per- formance. A combined score representing internal attributions was used for thisanalysis. Athletes rated on a 9-point scale how much each of six factors influencedtheir performance: ability, effort, readiness for competition, ability of other gym-nasts, difficulty of the routines, and luck. The scores for ability, effort, and read-iness for competition were added together to create an internal attribution score.Significant correlations were demonstrated

the predicted direction between SC-

trait and internal attributions

as well as competitive orientation

and internal attri-

butions (see Table 4). A significant main effect for SC-trait emerged, F(l, 43)^ =^

.002, as high SC-trait athletes (M

=^

= 3.41) elicited

Sport-Confidence

and

Competitive Orientation

/^^237

more internal attributions than low SC-trait athletes (M

=^

=

Also, performance-oriented

athletes (M

=^

1.71) were more inter-

nal in their attributions than outcome-oriented athletes (M

=^

=^

F(l, 43)

=

.001. Although no interaction effect emerged in this anal-

ysis to support Hypothesis 5, both SC-trait and competitive orientation weredemonstrated to influence athletes' attributional patterns.

These results support Weiner (1979), who states that success attributed internally is related to pride, confidence, and satisfaction. Other researchers

have

supported a relationship between internal attributions and self-confidence (Coving-ton

Beery, 1976; Fyans

Maehr, 1979; Gilmor

Minton, 1974). The rela-

tionship between attributions and sport-confidence is very significant. It seemsthat athletes use attributions to obtain feedback about their performance that isintricately related to perceptions of ability and feelings of competence and success.

The relationship between performance orientation and attributions is also significant. These results indicate that performance orientations may allow ath-letes to take personal responsibility

for their performance irrespective of outcome.

This finding is consistent with the positive relationship

between performance orien-

tation and internal locus of control (Rotter, 1966)demonstrated in the concurrentvalidity phase.

The second subjective outcome examined was perceived success, or the percentage of past sport experiences in which athletes perceived they had beensuccessful. Only SC-trait

was significantly related to perceived success (see Ta-

ble 4). Analysis of variance indicated a main effect only for SC-trait, F(l, 43)^ =^

.001, as high SC-trait athletes (M

=^

= 9.38) perceived

they had been more successful than low SC-trait athletes (M

71.30). Thus,

no interaction effect emerged to support Hypothesis

as only SC-trait signifi-

cantly influenced perceived success.

Performance

rating is another subjective outcome hypothesized to be related

to SC-trait and competitive orientation.

significant relationship emerged be-

tween performance orientation and performance rating, but no relationshipemerged between SC-trait and performance rating (see Table 4). Analysis of var-iance indicated that performance-oriented athletes (M

1.64) rate

their performance higher than outcome-oriented athletes (M

=^

=^

F(l, 43)

=^

.001. No main effect for SC-trait or interaction between

SC-trait and competitive orientation emerged for these data to support Hypothe-sis 7.

However, these results demonstrate that higher self-perceptions of perfor- mance are related to performance orientation. This is significant because

performance has a much greater impact upon cognitions and behavior than actual performance. By defining success and competence as performing well, ath-letes increase their chances of being successful. And as demonstrated by theseresults, how success is defined is even more crucial than level of confidence (SC-trait) in assessing self-performance.

The fourth subjective outcome examined in relation to the model of sport- confidence was perfomance satisfaction. Simple correlational analyses indicatedthat performance satisfaction was significantly related to performance orienta-tion (see Table 4). No relationship emerged between performance satisfactionand SC-trait. Again in the analysis of variance, no interaction between SC-trait

Sport-Confidence

and

Competitive Orientation

I^

I^

I

Figure

Performance based on the interaction of SC-trait and competitive orien-

tation. the evidence supports a sound theoretical framework and valid operationaliza-tions of the constructs within the conceptual model.

SC-trait and competitive orientation emerged as significant predictors of precompetitive and postcompetitive SC-state as well as several subjective out-comes. Perhaps the key finding of the study was that high SC-trait

performance-

oriented athletes were significantly higher in SC-state than

other groups. This

finding suggests that the interaction of athletes' individual d e f d t i o of successwith perception of their ability is related to their self-confidence

when competing.

Although it was disappointing

that precompetitive SC-state did not predict

performance, it seems that this relationship will remain questionable until SC-state can be measured at a time nearer to or during competition. Also, the inves-tigator felt that the elite nature of the sample and the importance

of this particular

competition may have influenced precompetitive

measures. The elite sample had

an extremely high mean and low standard deviation for the precompetitive SC-state measure (see Table

It seems likely that world-class athletes at a national

championship would not consciously admit to feelings of diffidence. Clearly, amajor problem in field research is controlling

the extraneous factors that impinge

^1 Vealey upon sport behavior. As seen in the validation model (see Figure

this study

was hampered by the failure to control Links

5 and 12. Additional testing of the

model is needed that employs designs and methodologies to accurately measureSC-state immediately prior to and during competition and to gain more preciseperformance measures. Performance

did emerge as a significant predictor of post-

competitive

SC-state, suggesting that athletes quickly internalize feelings of com-

petence and success based on their performance.

The serendipitous finding that the interaction of SC-trait and competitive orientation significantly influenced performance warrants careful interpretation.Although SC-trait and competitive

orientation proved to be better predictors than

SC-state in this study, these results are too premature to warrant modificationsin the conceptual model. Overall, however, these findings suggest that it is im-portant to understand not only how confident athletes are in sport, but also uponwhat their confidence is based.

Sport psychologists may bemoan the conceptualization

of another self-con-

fidence construct when research is currently divided into the areas of self-efficacy,perceived competence, and expectancy. However, the conceptualizationof sport-confidence originated in this study is not intended to add further "chaos in thebrickyard7' (Forscher, 1963)

but to enhance parsimony in the field of sport psy-

chology by conceptualizing self-confidence as specific

and unique to sport. Sport-

confidence and competitive orientation have been developed in order to draw fromthe various areas studying self-confidence

and build a situation-specific

theoreti-

cal framework that will help sport psychologists understand and predict behaviorin sport.

Following the method of strong inference suggested by Landers (1983), relationships

depicted in the conceptual

model of sport-confidence

need to be sub-

jected to alternative

explanations and theoretical modifications. Although evidence

was obtained to support the constructs in the model, construct validity is a psy-chometric property that is never proven. Rather, it is inferred from the accumu-lation of evidence. Additional research is needed to replicate these proceduresin order to build upon, modify, and extend the findings of this study.

Anastasi,

A.

Psychological testing.

New York: Macmillan.

Bandura,

A.^

(1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change.

Psy-

chological Review,

Bandura,

A.,

Reese,

&^ Adarns, N.E. (1962). Microanalysis

of action and fear arousal

as a function of differential levels of perceived self-efficacy.

Journal of Personality

and Social Psychology,

Corbin, C.B. (1981). Sex of subject, sex of opponent, and opponent ability as factors

affecting self-confidence

in a competitive situation.

Journal of Sport Psychology,

Corbin, C.B., Landers, D.M., Feltz,

D.L.,

&^ Senior,

(1983). Sex differences

in per-

formance

estimates:

Female lack of confidence

vs. male boastfulness.

Research Qzuzr-

terly for Exercise and Sport, 54,

Corbin, C.B.,

&^ Nix, C. (1979). Sex-typing of physical activities and success predictions of children before and after cross-sex competition.

Journal of Sport Psychology,