Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Prepare for your exams

Study with the several resources on Docsity

Earn points to download

Earn points by helping other students or get them with a premium plan

Community

Ask the community for help and clear up your study doubts

Discover the best universities in your country according to Docsity users

Free resources

Download our free guides on studying techniques, anxiety management strategies, and thesis advice from Docsity tutors

The shift in religious landscape in Western Europe since the 1960s, focusing on the decline of traditional Christian religion and the rise of spirituality. the theories of Davie and the operationalization of spiritualization of religion, presenting data on trends in spiritual religion, traditional Christian religiosity, church attendance, and traditional Christian beliefs. The study aims to test the hypotheses that the relationship between traditional Christian beliefs and church attendance, as well as spiritual religion and traditional Christian religiosity, has weakened in countries with the lowest levels of traditional Christian religiosity.

Typology: Study notes

1 / 41

This page cannot be seen from the preview

Don't miss anything!

‘Believing without Belonging’ in Twenty European Countries ( 1981 - 2008 ) De-institutionalization of Christianity or Spiritualization of Religion?^1 [Forthcoming in: Review of Religious Research, 2020] Paul Tromp, Anna Pless and Dick Houtman 2 Abstract Extending and building on previous work on the merits of Grace Davie’s theory about ‘believing without belonging’, this paper offers a comparative analysis of changes in the relationships between ‘believing’ and ‘belonging’ across countries. In doing so, two renditions of the theory that co-exist in Grace Davie’s work are distinguished, i.e., the typically foregrounded version about a de-institutionalization of Christianity and its often unnoticed counterpart about a spiritualization of religion. Societal growth curve modelling is applied to the data of the European Values Study for twenty European countries ( 1981 - 2008 ) to test hypotheses derived from both theories. The findings suggest that the typically foregrounded version of a de-institutionalization of Christianity needs to be rejected, while the typically unnoticed version of a spiritualization of religion is supported by the data. (^1) We are grateful to Peter Achterberg, Bart Meuleman, Rudi Laermans, Staf Hellemans, Klaus Friedrich, Erwin Gielens, and Galen Watts for their helpful remarks, and to Hellen Brans for her unconditional support. Draft versions of this paper were presented during Cultural Sociology Lowlands (University of Amsterdam, 20 June 2017) and the Annual Meeting of the Association for the Sociology of Religion (Montreal, 14 August 2017). Final versions of this paper were presented during the KOSMOI symposium (KU Leuven, 12 October 2018) and the SSSR+RRA Annual Meeting (Las Vegas, 27 October 2018). This article is part of the first author’s PhD project on religious decline and religious change in Western Europe (1981-2008), funded by KU Leuven. (^2) All authors are based at the Centre for Sociological Research (CeSO), KU Leuven, Belgium Parkstraat 45, 3000 Leuven, Belgium. Please direct all correspondence to the first author (Paul.Tromp [at] kuleuven.be) and/or the last author (Dick.Houtman [at] kuleuven.be).

Keywords Believing without belonging, religious change, religious decline, traditional Christian religiosity, spirituality, mysticism

1. Introduction In her seminal work Religion in Britain since 1945, better known under the motto in its subtitle: Believing without Belonging , Grace Davie (1994) has influentially critiqued the notion of an unambiguous decline of religion. Distinguishing between ‘believing’ and ‘belonging’, she defends the argument that in Britain since World War II, and more generally in Western Europe, “[b]elieving (…) persists while belonging continues to decline – or, to be more accurate, believing is declining (has declined) at a slower rate than belonging.” (Davie 1990a, 455) Davie’s ‘believing without belonging’ thesis sparked a lot of scholarly attention, and previous studies have already addressed vital elements of the theory in a range of different contexts. The current paper builds on and extends these earlier contributions by using them as vital and indispensable building blocks for a comparative analysis of the relationships between ‘believing’ and ‘belonging’ across place and time. So, in this paper, we study whether the relationship between ‘believing’ and ‘belonging’ has weakened in those European countries in which ‘belonging’ is lowest. We will answer this question by making use of the four available waves of the European Values Study (EVS), covering a time period of nearly three decades ( 1981 - 2008 ), and a geographical area of twenty European countries. This article proceeds as follows. In section 2, we will set out Davie’s ‘believing without belonging’ thesis, but as will become immediately clear, ‘believing without belonging’ is not one unambiguous thesis but in fact comprises two different theories on

dominance, appeal and legitimacy, especially in the northern and western parts of Europe (e.g. Norris and Inglehart (2011)). Historically rooted in the counterculture of the 1960s (Roszak 1969), a decidedly post-Christian / New Age spirituality emerged and spread in roughly the same time period and geographical area (Campbell 2007, Hanegraaff 1996, Heelas 1996). Various scholars, students of religious change in the West like Davie, have interpreted these recent developments as a shift from religion to spirituality. Heelas et al. (2005) for instance suggest that a ‘spiritual revolution’ may be unfolding, one in which the ‘life-as religion’ of the ‘congregational domain’ is increasingly giving way to the ‘subjective-life spirituality’ of the ‘holistic milieu’. Building on Troeltsch's (1956[1931]), Campbell (1978) similarly understands these recent changes in terms of a shift towards ‘spiritual and mystic religion’, which he has more recently portrayed as a “fundamental revolution in Western civilization” that entails a gradual ‘Easternization of the West’, i.e. a process in which a basically monistic Eastern worldview gradually replaces its dualistic counterpart that has historically characterized the West (Campbell 2007, 41). What the above-mentioned scholars have in common is that they all understand these processes of religious change as epitomized by the emergence and spread of a decidedly post-Christian / New Age spirituality that differs profoundly from traditional Christian religion as the West has known it for centuries (Houtman and Tromp 2020, Houtman, Aupers, and Heelas 2009). Adherents of such a post-Christian spirituality tend to self-identify as ‘spiritual but not religious’ and in doing so drive a wedge between ‘religion’ and ‘spirituality’, understanding the two as incompatible, firmly rejecting the former and embracing the latter. More specifically, they embrace a more individualized and subjective spirituality that prioritizes spiritual feeling and direct experience of the divine over Christianity’s institutional, doctrinal and ritual aspects

(Hammer 2001, Heelas 1996, Houtman and Tromp 2020, Roof 1993, Zinnbauer et al. 1997). Indeed, they distance themselves both from the institutional church as well as from traditional Christian dogmas and doctrines (Nicolet and Tresch 2009, Roof 1993), because the problem with organized religions is in their understanding that the latter are “preventing rather than facilitating a personal experience of the transcendent.” (Turner et al. 1995, 437) For these ‘highly active seekers’ (Roof 1993), spiritual feelings and experiences are hence divorced from, and no longer associated with, organized religion (Zinnbauer, Pargament, and Scott 1999), i.e. “neither [with] the Church nor God as represented by theistic Christianity.” (Palmisano 2010, 238) Indeed, many students of religion have meanwhile pointed out the emergence and growth of a spirituality that has completely broken away from religion, with the erosion of a church-based and belief-oriented religion giving rise to an individualized and experience-oriented spirituality (Ammerman 2013, Campbell 1978, De Groot and Pieper 2015, Flanagan and Jupp 2007, Marler and Hadaway 2002, Mears and Ellison 2000, Pollack 2008, Roof 1993, 1998, Versteeg 2006, Zinnbauer and Pargament 2005, Zinnbauer et al. 1997, Zinnbauer, Pargament, and Scott 1999). Davie’s theory about believing without belonging has however typically been interpreted as addressing something completely different from this, i.e. as referring merely to a de-institutionalization of Christianity – a decline in church attendance with many of those concerned nonetheless sticking to traditional Christian beliefs. Yet, observers like Voas and Crockett (2005) have correctly pointed out that a close reading of Davie’s book reveals that it does in fact feature two markedly different theories about increases in believing without belonging. The second rendition of her theory, which has more often than not remained unnoticed, does indeed address precisely the type of spiritualization of religion that we have just discussed.

accounts of secularization as a decline of religion are “getting harder and harder to sustain,” (Idem, 7 ) because it is in fact “more accurate to describe late-twentieth century Britain – together with most of Western Europe – as unchurched rather than simply secular.” (Idem, 12 - 13 ) The first theory that Davie brings forward here is hence a theory about de-institutionalization of Christianity: people do not cease to hold traditional Christian beliefs, but increasingly do so without (regularly) attending their churches’ services. Many scholars have taken ‘believing without belonging’ to mean precisely this, which is another way of saying that this first theory has pretty much become the ‘standard interpretation’ of ‘believing without belonging’ (Winter and Short 1993, Glendinning 2006, Nicolet and Tresch 2009, De Groot and Pieper 2015, Reitsma et al. 2012, Inglis 2007, Aarts et al. 2008). Whereas some scholars conclude, for Britain at least, that this version of ‘believing without belonging’ is empirically untenable (Voas and Crockett 2005), others find that this particular way of being religious is prevalent in the United States (Zinnbauer, Pargament, and Scott 1999) and Switzerland (Nicolet and Tresch 2009) and relatively popular in the Netherlands (De Groot and Pieper 2015). While previous studies have already addressed important aspects of this first rendition of the theory in a range of different contexts, we argue that a full-blown test necessitates a combination of three crucial elements that has thus far been neglected. Firstly, believing and belonging should be studied simultaneously, because what is crucial for the theory is precisely the relationship between the two (Davie 1990a, 455). Secondly, in addressing this relationship the focus should be on multiple points in time, so on how it changes over time, with the theory predicting a decline (Idem). Thirdly and finally, it should be studied whether this relationship has indeed weakened over time in the countries where ‘belonging’ is lowest. For it is precisely the notion that a decline in ‘belonging’ incites the weakening of the relationship between the two that raises Davie’s

argument above the status of a mere descriptive claim to that of a veritable theory that uncovers a causal chain. We elaborate on each of these three vital elements below. Firstly, instead of examining relationships between ‘believing’ and ‘belonging’, many of the existing studies (including Davie’s own) address their aggregated volumes, either for one moment in time or across time (Inglis 2007, Davie 1990a, b, 1994, 1997, Lambert 2004, Pollack and Pickel 2007, Voas and Crockett 2005, Winter and Short 1993 ). Davie herself for instance presents data for the proportions of the British and Western-European populations that attend church monthly (1990b, 405) on the one hand (‘belonging’) and belief in (a personal) God, sin, soul, heaven, life after death, the devil, and hell on the other (‘believing’) (Davie 1990a, 460, 1990b, 405). Based on these statistics alone, however, no solidly grounded inferences can be made about the de- institutionalization of Christianity, because this does not necessarily imply that a more drastic decline in belonging as compared to believing has weakened the link between the two. The same problem holds for Winter and Short (1993, 640) who assert that 'believing and belonging' is in fact a more accurate description of the religious situation in rural England, based on their observations that in 1990, 88% of their sample belongs to a church, denomination or religion; that 42% believes in life after death; and that 25% “claimed some form of religious or spiritual experience.” Indeed, Voas and Crockett (2005) claim precisely the opposite, namely that religion in Britain can be characterized as ‘neither believing nor belonging’. They base this claim on their findings that belief and church attendance demonstrate equal rates of decline in their panel data, while belief has even declined more rapidly than attendance in their cross-sectional data. Pollack and Pickel ( 2007 ) make the same claim on the basis of their finding that both church attendance and belief in God have declined. The point to underscore is that all these claims about the tenability of this first rendition of Davie's theory are based on

over time. The same holds for Reitsma et al. ( 2012 ), who derive hypotheses from modernisation theory to study the relationships between ‘believing’ and ‘belonging’ across countries, but not over time. They also derive hypotheses from religious market theory to study the relationships between the two over time and across countries, to be sure, but in doing so they compare western countries with former communist ones^3 rather than countries with higher respectively lower levels of church attendance. In sum, it is evident that previous studies have already addressed vital elements of the first rendition of Davie’s theory about increases in believing without belonging, i.e., the theory about a de-institutionalization of Christianity, in a range of different contexts. To the best of our knowledge, however, the key hypothesis to be derived from this theory has thus far not been tested yet, i.e. that the relationship between traditional Christian beliefs and church attendance has declined in those European countries in which church attendance is lowest (Hypothesis 1).

distinction, yet have like Voas and Crockett ( 2005 ) themselves only tested the ‘strong version’ of ‘believing without belonging’, leaving the ‘weak interpretation’ to remain untested at all. Indeed, at various points in her book, Davie puts forward different sets of meanings of ‘believing’ and ‘belonging’. The second rendition of her theory comes to the fore most clearly where she points out how in Britain and Western Europe more generally “feelings, experience and the more numinous aspects of religious belief demonstrate considerable persistence,” whereas “ religious orthodoxy , ritual participation and institutional attachment display an undeniable degree of secularization (…) both before and during the post-war period.” (Davie 1994, 4-5, italics added) This second version of Davie’s theory is hence not about people leaving the church, while sticking to their traditional Christian beliefs (i.e. de-institutionalization of Christianity as discussed above), but about people prioritizing spiritual feelings and experiences of the divine over Christianity’s institutional, ritual and doctrinal aspects. This is the type of religion that the German theologian Ernst Troeltsch (1956[1931]) understands as ‘mystical’ religion. Despite the fact that the latter has traditionally been neglected in the sociology of religion (Daiber 2002, 329), it has meanwhile been picked up by contemporary sociologists of religion to interpret recent changes in the religious landscapes of the West as increases in ‘religious individualism’ (Bellah et al. 2008[1985], Campbell 1978, Daiber 2002, Streib and Hood 2011) “Mysticism,” as Troeltsch himself describes it, “shows a strong impulse towards the directness, presence, and inwardness of the religious experience, towards a direct contact with the divine, a contact which transcends or supplements traditions, cults, and institutions.” (1911, 172) In Troeltsch’s understanding, if mysticism ‘transcends’ rather than ‘supplements’ religion, it has broken away from religious traditions and

countries: Austria, Belgium, Croatia, Denmark, Finland, France, Great Britain, Greece, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and West-Germany. All twenty countries had data available for all four waves except for Austria, Croatia, Finland, Greece, Luxembourg, and Portugal who were not yet included in 1981. In addition, Croatia, Greece, and Luxembourg were not yet included in 1990 either, and Norway had one missing wave in 1999. This resulted in a dataset with 87,153 individuals distributed over seventy country-year combinations. The average number of respondents per country-year combination is 1,245 (SD = 467) with a minimum of 304 in Northern Ireland ( 1990 ), and a maximum of 2,792 in Belgium ( 1990 ).

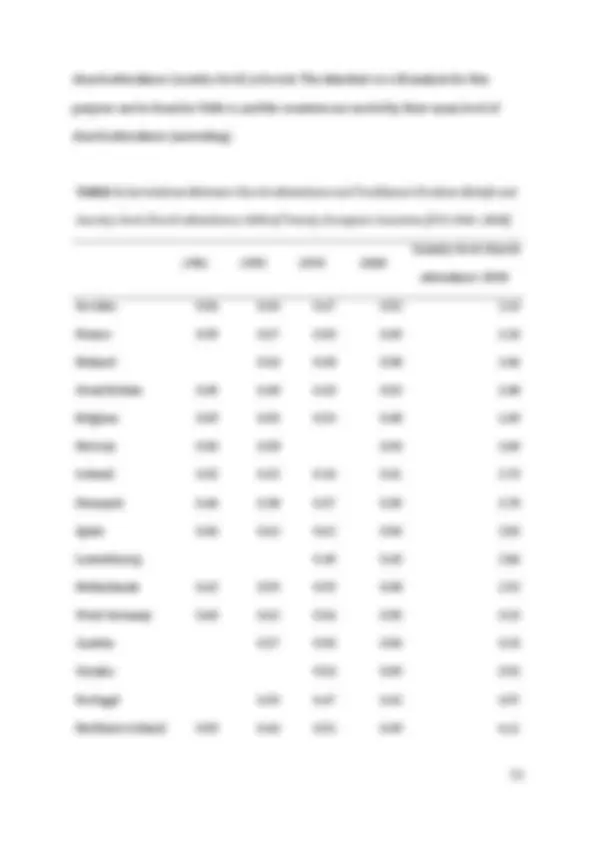

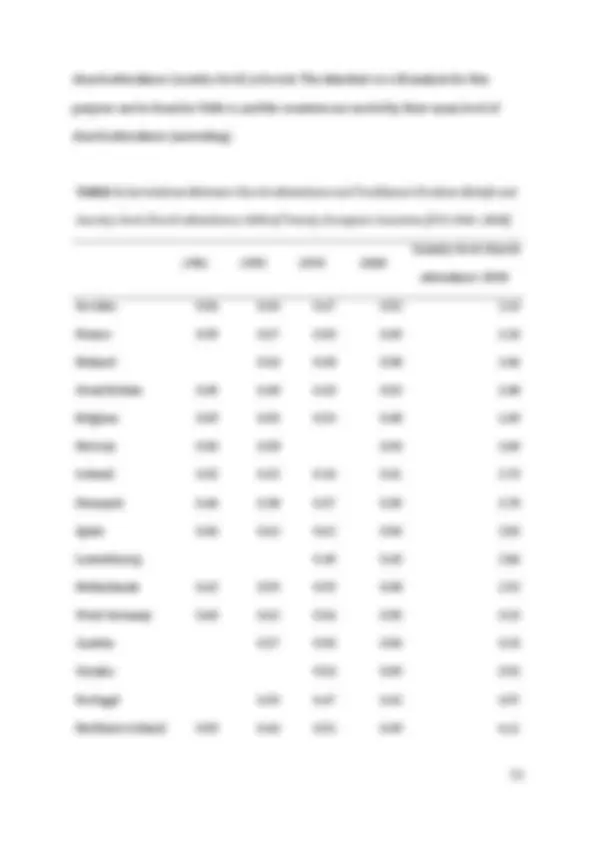

subsumed under one component (see Table 1). All five items had high and positive loadings on the first factor and could reliably be combined to form one scale (Cronbach’s alpha =. 843 )^5. Scale scores are assigned as mean item scores for those with at least three valid answers, resulting in a valid N of 80,334 respondents (92.2%)^6. TABLE 1 Factor Loadings of Five Items Measuring Traditional Christian Beliefs (N = 63,527) Items Component 1 Personal God. Life after death. Hell. Heaven. Sin. Eigenvalue 3. % of Variance 61.8% Church attendance is measured with the question: Apart from weddings, funerals and christenings, about how often do you attend religious services these days? Response options comprise 1 ‘more than once a week’, 2 ‘once a week’, 3 ’once a month’, 4 ‘only on (^5) Iceland and Norway have respectively the lowest and highest Eigenvalues (2.124 and 3.256) and proportions explained variance (42.5% and 65.1%). The factor loadings varied from .57 to .82 (Iceland), and from .79 to .86 (Norway). Iceland and Norway have respectively the lowest and highest Cronbach’s alpha’s (.656 and .865). Only in Croatia and Malta will the alpha increase slightly if the item about a Personal God is deleted from the scale (from .830 to .875 in Croatia, and from .725 to .814 in Malta). (^6) If we set the minimum to four or five valid answers, we will lose respectively 13% and 27% of the sample. This is due to relatively high proportions of missing values for the items belief in life after death (16.1%), heaven (11.9%), hell (11.5%), and sin (9.4%). Nearly all respondents who have a missing value on one or more of these questions answered them with “I don’t know”.

Country-level traditional Christian religiosity is computed for each country separately by taking the average level of traditional Christian religiosity in that country in the year 20 08 (i.e. EVS wave 4). Finally, we need a measure for spiritual religion but this is easier said than done as questions about spirituality in general, and spiritual feelings and experiences of the divine in particular, are virtually absent in today’s large internationally comparative survey programs, and the European Values Study is no exception (Houtman, Heelas, and Achterberg 2012). Though it is clear that there is no way to tackle this methodological shortcoming in a fully convincing manner, we selected a question about taking moments for prayer, meditation or contemplation – spiritual practices typically used for “turning inward,” (Campbell 2007, 65) “direct experience of ‘the real’,” (Idem, 67) or “direct contact with the divine.” (Troeltsch 1911, 172) “[S]uch practices often lead to an experience of connectedness with a larger reality, yielding a more comprehensive self; with other individuals or the human community; with nature or the cosmos; or with the divine realm.” (Huss 2014, 49 - 50) The exact wording of the question we use is: Do you take some moments of prayer, meditation or contemplation or something like that? Respondents could answer this question with 1 ‘yes’, or 0 ‘no’. The advantage of using this single item to measure spiritual religion is that prayer, meditation and contemplation are being practiced both within and without a traditional Christian context (Ammerman 2013, Berghuijs, Pieper, and Bakker 2013, Huss 2014, Lucas 1992, Pargament et al. 1995, Schlehofer, Omoto, and Adelman 2008, Versteeg 2006, Woodhead 2011, Zinnbauer 1997). For meditation is not only a popular practice among New Agers (Donahue 1993, Huss 2014, Lucas 1992) but also among visitors of a Jesuit spiritual center in the Netherlands (Versteeg 2006). Alongside prayer it is moreover not only embraced by charismatic-evangelical Christians, but also by Catholic and

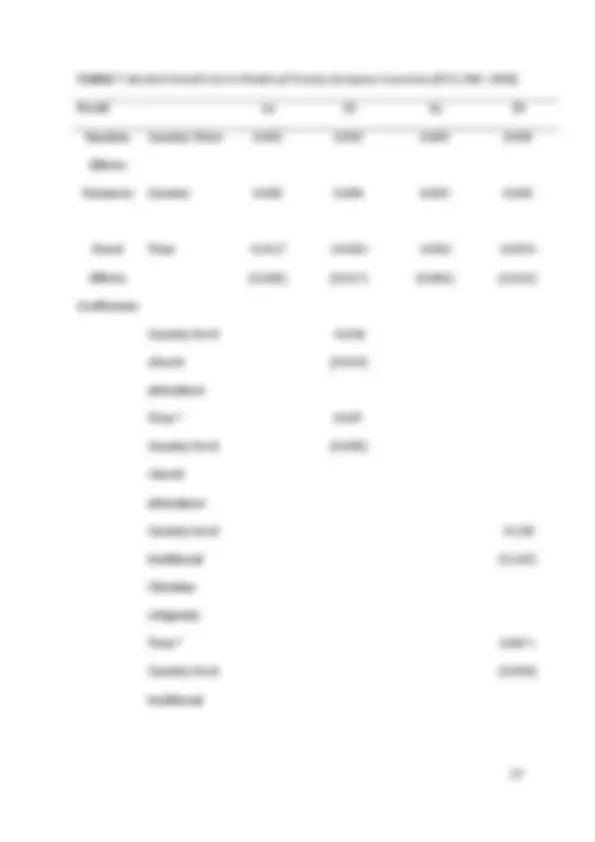

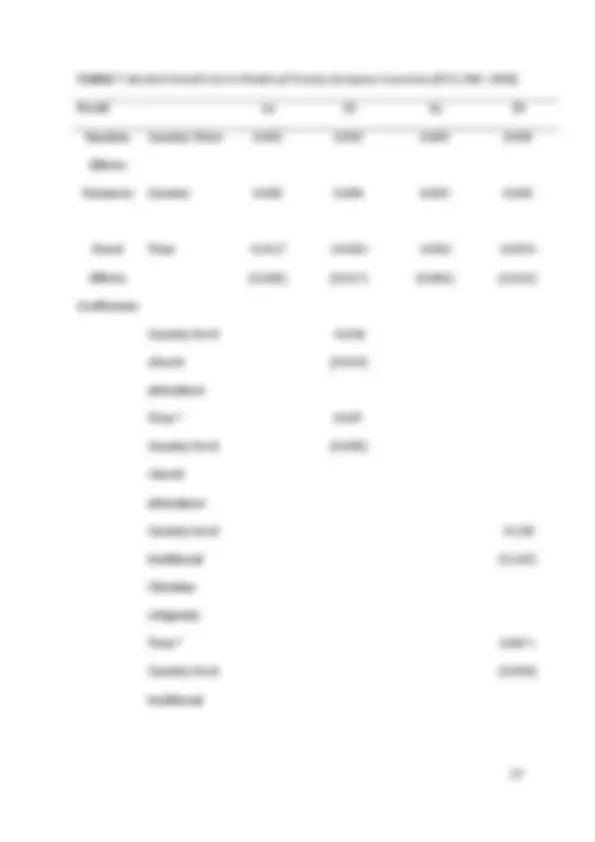

Protestant churches considered mainstream and historic (Woodhead 2011). If the relationship between spiritual religion and traditional Christian religiosity does indeed weaken across time, as Davie’s theory about spiritualization of religion predicts, experience-oriented spirituality has become increasingly disconnected from traditional Christian institutions and doctrines. See Table 2 for the descriptive statistics of all the variables that will be included in our models. We also include the general trends of all the scales, and of all the variables that are used to construct these scales, so as to provide the reader with a more complete picture of how the various religiosity indicators behave over time (see Table 3 ). TABLE 2 Descriptive statistics N MIN MAX M SD a Spiritual religion

h (^) Denmark and Malta have respectively the lowest and highest country-means for this variable (. and .94). With 9.4%, the average proportion of missing values is relatively high for this item (minimum = 4.1% in Malta, and maximum = 17.9% in Finland). i (^) Data are unavailable for ten country-year combinations, hence the valid N = 70. TABLE 3 Trends of all the variables (EVS 1981-2008, Twenty European Countries) 1981 1990 1999 2008 absolute change relative change Spiritual religion

Researchers often use growth-curve models to analyse individual-level panel data, i.e. the same individuals are measured on multiple occasions, a structure that implies a multilevel model in which the measurement occasions are nested within the individuals. Growth-curve models can be used to study whether an independent variable x causes change in a dependent variable y over time, and this predictor variable x can either be time-variant (such as age) or time-invariant (such as gender). In the dataset that we use, the European Values Study (1981-2008), all the individuals are only measured once, however, the same countries are measured up to four times. Taking societies as the units of analysis, societal growth curve modelling can be used to examine “whether the absolute level of some time-invariant (…) [independent] variable xj leads to faster or slower change in [dependent variable] y. (…) An xj variable (…) could be the country mean 𝑥̅𝑗̇ (…), though it could also denote some other time-invariant macro-level characteristic.” (Fairbrother 2014, 125). Subsequently, an interaction term between the independent variable xj and time needs to be added to the model. We will treat the twenty countries in our sample as ‘individuals’, each of them measured on two, three, or four occasions (i.e. the number of available EVS waves). This implies that country-waves are nested within countries. The models require the inclusion of a time-invariant predictor variable ( xj) , and an interaction term between the latter and time. Needless to say, the model therefore also requires the inclusion of a main effect of time. To test our first hypothesis, the required dependent variable y should express the relationship between two variables. Hence, we will calculate for each country-wave combination a unique Pearson’s correlation coefficient between traditional Christian beliefs and church attendance. The required xj variable is country-level church attendance. In sum, we will test whether the correlation between traditional Christian beliefs and church attendance has weakened in those European countries in which